- Professor MSO, VIVE

- Associate Professor, University of Bristol

- Research Fellow, IZA

- Co-editor: Economics of Education Review

- Projects:

- Contact: mail@hhsievertsen.net

- Download: CV

Hans Henrik Sievertsen

-

"Parental Minimum Wages, Children's Education, and Racial Inequality"

with Christine Valente and Luyang Chen

- Status: Submitted (December 2024)

- Downloadworking paper

- Abstract:We test whether having a parent covered by minimum wages improves long-term education outcomes. We exploit variation in exposure to the 1966 Fair Labor Standards Act by child birth cohort and predetermined parental occupation. Parental minimum wage coverage during children’s teenage years increases children’s completed education. This effect is larger among black children, contributing to lowering educational inequality. This comes primarily from relaxed household budget constraints. First, education effects are larger for groups experiencing larger first-generation wage increases. Second, suggestive evidence indicates reduced teenage labor force participation and a reduction in dropout due to financial difficulties, especially for black children.

"Playing the system: address manipulation and access to schools"

with Andreas Bjerre-Nielsen, Lykke Sterll Christensen, and Mikkel Høst Gandil

- Status: Submitted (July 2024)

- Downloadworking paper

- Read media coverage:Weekendavisen (in Danish), Berlingske (in Danish)

- Abstract:Policymakers and academics often treat eligibility as exogenous in allocation mechanisms. For example in school choice, researchers focus on preference manipulation but view traits determining eligibility as constant. We develop a model that integrates trait manipulation in school choice and assess its predictions empirically. Using an admission reform, we find that increasing the importance of applicants' addresses doubled address changes. Among those not enrolling in their top choice, 26% were displaced due to others' trait manipulation. This novel justified envy is 50% higher than the justified envy from preference manipulation. Displaced applicants attend schools with 0.08 SD lower peer GPA.

"Saving neonatal lives at scale: lessons for targeting"

with Christine Valente and Mahesh C. Puri

- Status: working on it (July 2024)

- Downloadworking paper

- Abstract:Neonatal sepsis kills over 400,000 children annually. Experimental estimates of the preventive use of chlorhexidine vary widely, leading to external validity concerns. We provide the first quasi-experimental estimates of the effect of chlorhexidine in “real life” conditions and apply machine-learning (ML) to analyze treatment effect heterogeneity in a nationallyrepresentative, Nepalese observational dataset. We find that chlorhexidine decreases neonatal mortality by 43% and that a simple targeting policy leveraging heterogeneous treatment effects improves neonatal survival relative to WHO recommendations. Heterogeneous treatment effects extrapolated from our ML analysis are broadly in line with experimental findings across five countries despite significant implementation differences.

"Antibiotics in Early Childhood and Subsequent Cognitive Skills"

with Gerard J. van den Berg and Paul Bingley

- Status: we are working on it (June 2024)

- Abstract:In many situations antibiotics save lives and restore health, but in milder cases potential negative long-run effects might dominate the benefits. Evidence based on animal experiments suggests that usage at early ages can adversely affect the development of cognitive skills. Using Danish population-wide administrative data we study the causal effect of early-childhood antibiotic use on later school test results. Both variation in antibiotics use driven by GPs prescription propensity and variation between siblings suggest that higher antibiotics use in childhood causes worse schooling outcomes.

"Work and fertility in Norway over the last three decades "(current working title)

with Sara Cools and Marte Ström

"Household Responses to Unconditional Child Benefits"(current working title)

with Jonas Lau-Jensen Hirani, Rune Vammen Lesner, and Miriam Wüst

-

"Do female experts face an authority gap? Evidence from economics"

with Sarah Smith

Journal of Economic Behavior and Organisation, accepted.

- Downloadworking paper

- Abstract:This paper reports results from a survey experiment comparing the effect of (the same) opinions expressed by visibly senior, female versus male experts. Members of the public were asked for their opinion on topical issues and shown the opinion of either a named male or a female economist, all professors at leading US universities. There are three findings. First, experts can persuade members of the public – the opinions of individual expert economists affect the opinions expressed by the public. Second, the opinions expressed by visibly senior female economists are more persuasive than the same opinions expressed by male economists. Third, removing credentials (university and professor title) eliminates the gender difference in persuasiveness, suggesting that credentials act as a differential information signal about the credibility of female experts.

"The gender gap in expert voice: evidence from economics"

with Sarah Smith

Public Understanding of Science, accepted.

- Downloadworking paper

- Accessreplication files

- Abstract:Women's voices are likely to be even more absent from economic debates than headline figures on female under-representation suggest. Focusing on a panel of leading economists we find that men are more willing than women to express an opinion and are more certain and more confident in their opinions, including in areas where both are experts. Women make up 21 per cent of the panel but 19 per cent of the opinions expressed and 14 per cent of strong opinions. We discuss implications for the economics profession and for promoting a genuine diversity of views.

"The prevalence, trends and heterogeneity in maternal smoking around birth between the 1930s and 1970s"

with Stephanie von Hinke, Jonathan James, Emil Sørensen, and Nicolai Vitt

inBaltagi, B. and Moscone, F. (eds.) Recent Developments in Health Econometrics: A volume in honour of Andrew Jones [invited] (2024)

- Link to publisher

- Downloadworking paper

- AbstractThis paper shows the prevalence, trends and heterogeneity in maternal smoking around birth in the United Kingdom, focusing on the war and post-war reconstruction period in which there exists surprisingly little systematic data on (maternal) smoking behaviours. Within this context, we highlight relevant events, the release of new information about the harms of smoking, and changes in (government) policy aimed at reducing smoking prevalence. We show stark changes in smoking prevalence over a 30-year period, highlight the onset of the social gradient in smoking, as well as genetic heterogeneities in smoking trends.

"Beyond Treatment Exposure–The Impact of the Timing of Early Interventions on Child and Maternal Health"

with Jonas Lau-Jensen Hirani and Miriam Wüst

Journal of Human Resources (2024)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Abstract:This paper studies the impact of the timing of early-life investment policies on child and maternal health. We exploit variation induced by a nurse strike in Denmark, that resulted in a large-scale cancellation of home visits for families with infants. Combining unique nurse records with administrative data, we show that missing the early but not later visits increases subsequent child and mother contacts to health professionals. We show that likely mechanisms for these results include nurses’ focus on timely maternal mental health screening and information provision to new families.

"Grades and Employer Learning"

with Anne Toft Hansen and Ulrik Hvidman

Journal of Labor Economics (2024)

- Read media coverage: Weekendavisen (in Danish)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Access replication files

- Abstract:We identify the labor market returns to university grade point average (GPA) by leveraging a nationwide change in the scaling of grades in Danish universities. Our results show that a reform-induced increase in GPA that is unrelated to ability causes higher earnings immediately after graduation, but the effect fades in subsequent years. The effect at labor market entry is largest for individuals with fewer alternative signals. Although employers initially screen candidates on the basis of skill signals, our findings are consistent with a model in which employers rapidly learn about worker productivity.

"Assessments in Education"

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance [invited](2023)

- Download accepted version

- Link to publisher

- Access replication files

- Abstract:Assessments such as standardized tests and teacher evaluations of students' classroom participation are central elements of most educational systems. Assessments inform the student, parent, teacher, and school about the student learning progress. Individuals use the information to adjust their study efforts and to make guide their course choice. Schools and teachers use the information to evaluate effectiveness and inputs. Assessments are also used to sort students into tracks, educational programmes, and on the labor market. Policymakers use assessments to reward or penalise schools and parents use assessment results to select schools. Consequently, assessments incentivize the individual, the teacher, and the school to do well.

Because assessments play an important role in individuals' educational careers, either through the information or the incentive channel, they are also important for efficiency, equity, and well-being. The information channel is important for ensuring the most efficient human capital investments: students learn about the returns and costs of effort investments and about their abilities and comparative advantages. However, because students are sorted into educational programs and on the labor market based on assessment results, students optimal educational investment might not equal their optimal human capital investment because of the signaling value. Biases in assessments and heterogeneity in access to assessments are sources of inequality in education according to gender, origin, and socioeconomic background. These sources have long-running implications for equality and opportunity. Finally, because assessment results also carry important consequences for individuals' educational opportunities and on the labor market, they are a source of stress and reduced well-being.

"The Importance of External Assessments: High School Math and Gender Gaps in STEM Degrees"

with Simon Burgess, Daniel Sloth Hauberg, and Beatrice Schindler Rangvid

Economics of Education Review (2022)

- Access media coverage:View from the Lab (Podcast)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Access replication files

- Abstract:We exploit the random allocation to a semi-external assessment in Math (SEAM) at the end of high school in Denmark to test the effect of SEAM on subsequent enrollment and graduation in post-secondary education. We find that SEAM in high school reduces the gender gap in graduation from post-secondary STEM degrees. Our results show that cancelling SEAM, as was temporarily implemented in many regions during the COVID-19 pandemic, may impact human capital accumulation in the long run.

"Quasi-market competition in public service provision: user sorting and cream skimming"

with Thorbjørn Sejr Guul and Ulrik Hvidman

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory (2021)

- Access media coverage: UoB summary

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Access replication files

- Access teaching material

- Abstract:Quasi-markets that introduce choice and competition between public service providers are in-tended to improve quality and efficiency. This paper demonstrates that quasi-market competition may also affect the distribution of users. First, we develop a simple theoretical framework that distinguishes between user sorting and cream-skimming as mechanisms through which quasi-markets may lead to high-ability users becoming more concentrated among one group of provid-ers and low-ability users among a different group. Second, we empirically examine the impact of a nationwide quasi-market policy that introduced choice and activity-based budgeting into Dan-ish public high schools. We exploit variation in the degree of competition that schools were ex-posed to, based on the concentration of providers within a geographical area. Using a differ-ences-in-differences design—and register data containing the full population of students over a nine-year period (N=207,394)—we show that the composition of students became more concen-trated in terms of intake grade point average after the reform in high-competition areas relative to low-competition areas. These responses in high-competition regions appear to be driven both by changes in user sorting on the demand side and by cream-skimming behavior among public pro-viders on the supply side.

"Gender Disparities in Top Earnings: Measurement and Facts for Denmark 1980-2013"

with Niels-Jakob Harbo Hansen, Karl Harmenberg, and Erik Öberg

Journal of Economic Inequality (2021)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Access replication files

- Abstract:Extending the work of Atkinson et al. (2018), we decompose top-earnings gender disparities into a glass-ceiling coefficient and a top-earnings gender gap. The decomposition uses that both male and female top earnings are Pareto distributed. If interpreting top-earnings gender disparities as caused by a female-specific earnings tax, the top-earnings gender gap and glass-ceiling coefficient measure the tax level and tax progressivity, respectively. Using Danish data on earnings, we show that the top-earnings gender gap and the glass-ceiling coefficient evolve differently across time, the life cycle, and educational groups. In particular, while the topearnings gender gap has been decreasing in Denmark over the period 1980-2013, the glass-ceiling coefficient has been remarkably stable.

"High-Stakes Grades and Student Behavior"

with Ulrik Hvidman

Journal of Human Resources (2021)

- Access media coverage: JHR news

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Access replication files

- Abstract:High-stakes exams carry important consequences for the prospects of reaching university. This study examines whether the incentives associated with exam grades affect educational investments. Exploiting a reform-induced recoding of high school students’ grade point average, we identify the effect of high-stakes grades on student behavior. The results show that students who were downgraded by the recoding performed better on subsequent assessments. The increase in academic performance in high school translated into an increased likelihood of university enrollment. As the recoding did not convey information about actual performance, these results emphasize that incentives are important in understanding students’ educational investments.

"Maternity Ward Crowding, Procedure Use, and Child Health"

with Jonas Maibom, Marianne Simonsen, and Miriam Wüst

Journal of Health Economics (2021)

- Access media coverage: Weekendavisen (in Danish)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Abstract:This paper studies the impact of day-to-day variation in maternity ward crowding on medical procedure use and the health of infants and mothers. Exploiting data on the universe of Danish admissions to maternity wards in the years 2000-2014, we first document substantial day-to-day variation in admissions. Exploiting residual variation in crowding, we find that maternity wards change the provision of medical procedures and care on crowded days relative to less crowded days, and they do so in ways that alleviate their workload. We find very small and precisely estimated effects of crowding on child and maternal health. Thus our results suggest that, for the majority of uncomplicated births, maternity wards in Denmark can cope with the observed inside-ward variation in daily admissions without detectable health risks.

"Neonatal Health of Parents and Cognitive Development of Children"

with Claus Thustrup Kreiner

Journal of Health Economics (2020)

- Access media coverage: Danish National Research Foundation

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Abstract:It is well-established that neonatal health is a strong predictor of socioeconomic outcomes later in life, but does neonatal health also predict key outcomes of the next generation? This paper documents a surprisingly strong relationship between birth weight of parents and school test scores of their children. The association between maternal birth weight and child test scores corresponds to 50–80 percent of the association between the child’s own birth weight and test scores across various empirical specifications, for example including grandmother fixed effects thatisolate within-family differences between mothers. Paternal and maternal birth weights are equally important in predicting child test scores. Our intergenerational results suggest that inequality in neonatal health is important for inequality in key outcomes of the next generation.

"The Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire and Standardized Tests: Reliability across Respondent Type and Age"

with Maria Keilow, Janni Niclasen, and Carsten Obel

PLoS One (2019)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Abstract:Exploiting nation-wide data from the Danish National Birth Cohort, we show that children’s emotional and behavioral problems measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) are closely related to their performance in standardized academic tests for reading and mathematics in sixth grade. The relationship is remarkably linear across the entire distribution for both the total difficulties score and subscale scores of the SDQ; higher scores on the SDQ (more problems) are related to worse performance in academic tests. We assess the similarity across respondent type; parent (child age 7 and 11), teacher (child age 11) and self-reported scores (child age 11), and find that teacher and parent reported scores have very similar slopes in the SDQ–test score relationship, while the child reported SDQ in relation to the academic test performance has a flatter slope.

"The Socio-Economic Gradient in Children’s Test-Scores - A Comparison Between the U.S. and Denmark"

with Christopher Jamil de Montgomery

Nationaløkonomisk Tidsskrift (2019)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Abstract:This paper contributes to the debate on intergenerational mobility in the U.S. and Denmark by linking parental resources to differentials in cognitive development as they develop through primary and lower secondary school in each country. Using U.S. survey data and Danish register data, we observe a socio-economic gradient along the entire test score distribution in both countries, but the gradient is always largest in the U.S. The test-score difference between the above and below median household income groups at school entry is about 20 percent larger in the U.S. compared with Denmark. Our findings show that a substantial socio-economic test-score gradient is present even in a Scandinavian welfare state with universal child policies. However, in light of the recent debate on similarities in intergenerational mobility between Denmark and the U.S., it is important to note that the socio-economic gradient in test-scores is smaller in Denmark compared with the U.S.

"The Gift of Time? School Starting Age and Mental Health"

with Thomas S. Dee

Health Economics (2018)

- Access media coverage: New York Times, Stanford GSE, The Washington Post, The Seattle Times, Huffington Post, The Guardian, Quartz

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Abstract:Using linked Danish survey and register data, we estimate the causal effect of age at kindergarten entry on mental health. Danish children are supposed to enter kindergarten in the calendar year in which they turn 6 years. In a "fuzzy" regression-discontinuity design based on this rule and exact dates of birth, we find that a 1-year delay in kindergarten entry dramatically reduces inattention/hyperactivity at age 7 (effect size = –0.73), a measure of self-regulation with strong negative links to student achievement. The effect is primarily identified for girls but persists at age 11.

"Discharge on the day of birth, parental responses and health and schooling outcomes"

with Miriam Wüst

Journal of Health Economics (2017)

- Access media coverage: Weekendavisen (in Danish)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Access replication files

- Abstract:Exploiting the Danish roll-out of same-day discharge policies after uncomplicated births, we find that treated newborns have a higher probability of hospital readmission in the first month after birth. While these short-run effects may indicate substitution of hospital stays with readmissions, we also find that—in the longer run—a same-day discharge decreases children's ninth grade GPA. This effect is driven by children and mothers, who prior to the policy change would have been least likely to experience a same-day discharge. Using administrative and survey data to assess potential mechanisms, we show that a same-day discharge impacts those parents’ health investments and their children's medium-run health. Our findings point to important negative effects of policies that expand same-day discharge policies to broad populations of mothers and children.

"Discharge on the day of birth, parental responses and health and schooling outcomes"

with Francesca Gino and Marco Piovesan

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2016)

- Note: Gino was not involved in the data work. See The many co-authors roject

- Access media coverage: Scientific American, Forbes, Huffington Post, Phys.org, Harvard Business Review, BBC, Quartz , Daily Mail, NyMag, Spiegel (in German), Videnskab.dk (in Danish), Politiken (in Danish)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Access replication files

- Abstract:Using test data for all children attending Danish public schools between school years 2009/10 and 2012/13, we examine how the time of the test affects performance. Test time is determined by the weekly class schedule and computer availability at the school. We find that, for every hour later in the day, test performance decreases by 0.9% of an SD (95% CI, 0.7–1.0%). However, a 20- to 30-minute break improves average test performance by 1.7% of an SD (95% CI, 1.2–2.2%). These findings have two important policy implications: First, cognitive fatigue should be taken into consideration when deciding on the length of the school day and the frequency and duration of breaks throughout the day. Second, school accountability systems should control for the influence of external factors on test scores.

"Care around birth, infant and mother health and maternal health investments – Evidence from a nurse strike"

with Hanne Kronborg and Miriam Wüst

Social Science and Medicine (2016)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Abstract:Care around birth may impact child and mother health and parental health investments. We exploit the 2008 national strike among Danish nurses to identify the effects of care around birth on infant and mother health (proxied by health care usage) and maternal investments in the health of their newborns. We use administrative data from the population register on 39,810 Danish births in the years 2007–2010 and complementary survey and municipal administrative data on 8288 births in the years 2007–2009 in a differences-in-differences framework. We show that the strike reduced the number of mothers' prenatal midwife consultations, their length of hospital stay at birth, and the number of home visits by trained nurses after hospital discharge. We find that this reduction in care around birth increased the number of child and mother general practitioner (GP) contacts in the first month. As we do not find strong effects of strike exposure on infant and mother GP contacts in the longer run, this result suggests that parents substitute one type of care for another. While we lack power to identify the effects of care around birth on hospital readmissions and diagnoses, our results for maternal health investments indicate that strike-exposed mothers—especially those who lacked postnatal early home visits—are less likely to exclusively breastfeed their child at four months. Thus reduced care around birth may have persistent effects on treated children through its impact on parental investments.

"Local unemployment and the timing of post-secondary schooling"

Economics of Education Review (2016)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Abstract:Using Danish administrative data on all high school graduates from 1984 to 1992, I show that local unemployment has both a short- and a long-run effect on school enrollment and completion. The short-run effect causes students to advance their enrollment, and consequently their completion, of additional schooling. The long-run effect causes students who would otherwise never have enrolled to enroll and complete schooling. The effects are strongest for children of parents with no higher education.

"The exploitation of talent"

with Nicolaj Christiansen

Nationaløkonomisk Tidsskrift (2008)

- Link to publisher

- Download accepted version

- Abstract:This article is a review of the seminar paper Superstar Effect in Italian Football which was written for the seminar on sports economics at the Department of Economics, University of Copenhagen and awarded the McKinsey Award in spring 2008. Only the main findings from the seminar paper will be presented here. For details and technicalities we refer to the original seminar paper Christiansen and Sievertsen (2008), which can be downloaded at www.econ.ku.dk/nf/superstareffect.pdf. In short, superstar economics is the branch of labour economics that deals with the phenomenon of nonlinear and highly rightskewed income distributions, that is observed in certain activities. The puzzle is, that the most talented individuals in these activities can obtain extremely high salaries compared to their colleagues, even though they are only marginally more talented. Theoretical explanations of the puzzle are reviewed and the superstar phenomenon is analysed empirically on Italian football, where a significant superstar effect is found.

-

"Afgangsprøvernes betydning for overgangen til ungdomsuddannelserne"

with Eva Lundstrøm Lademann, Julie Schou Nicolajsen, and Beatrice Schindler Rangvid.VIVE - Rapport (2024)[in Danish]

- Downloadreport

-

"Forældres skolevalg i Bagsværd, Gladsaxe Kommune"

with Sarah Richardt SchoopVIVE - Rapport (2024)[in Danish]

- Downloadreport

-

"Afdækning af REFUD-muligheder på dagtilbudsområdet"

with Rune Vammen LesnerVIVE - Rapport (2024)[in Danish]

- Downloadreport

-

"En god start - Betydningen af alder ved skolestart for barnets udvikling"

SFI - Rapport, 15:38 (2015)[in Danish]

- Downloadreport

- Downloadupdated results

-

"Børn i Lavindkomstfamilier"

with Christopher Jamil de Montgomery

SFI - Rapport, 15:22 (2015)[in Danish]

- Downloadreport

-

-

"Det økonomiske fundament: Finansiering og faktorer med betydning for omkostningerne"

with Ulrik Hvidman

Chapter 4 in"Styring, ledelse og resultater på ungdomsuddannelserne". Redigeret af Lotte Bøgh Andersen, Peter Bogetoft, Jørgen Grønnegård Christensen, Torben Tranæs. Syddansk Universitetsforlag 2014[in Danish]

- Downloadbook

-

-

"Infrastruktur og Danmarks internationale konkurrenceevne: et strategisk oversigtsstudie"

with Ole Kveiborg

Technical University of Denmark, DTU Transport; Nr. 7 (2010)[in Danish]

- Downloadreport

-

Reports and book contributions

- 30-07-2024:"Hvorfor skal ansøgeren med den højeste karakter egentlig stå forrest i køen?"

with Mikkel Høst Gandil

Politiken - 29-11-2023: "How do the views of experts and the public differ on big policy questions?"

with Sarah Smith

Economics Observatory - 08-03-2022: "How can we give women equal voice in economics?"

with Sarah Smith

Economics Observatory - 13-11-2020: "Learning loss: the National Tutoring Programme"

with Simon Burgess

The Conversation

Read media coverage: Financial Times

UNESCO estimates that around 1.5 billion children were unable to attend school in the spring of 2020. Closed schools mean lost learning, lower skills and reduced life chances and wellbeing.

A strategy for closing this learning gap needs to be rapid, school-based rather than online, and provided in addition to regular school. Given the size of the learning gap, it requires significant investment. Most importantly, there must be evidence of its effectiveness. The policy that best fits these criteria is small-group tutoring, based in schools. This is the focus of the UK government’s new flagship catch-up programme, available to state schools in England.

Unequal outcomes

Education losses would be less serious if families had been able to compensate for school closures with effective home learning, but this requires at least a quiet study space and a person that can help. Unsurprisingly, access to such environments is highly unequal. We believe in experts. We believe knowledge must inform decisions The early evidence backed this up, showing both general learning loss and that the effect is greatest in disadvantaged households.

Now children are back in school, researchers can start to measure the loss of learning. A study in the Netherlands estimates that students lost a fifth of a year of schooling. Evidence suggests that the losses in England are also dramatic.

In June, the UK government announced a £1 billion COVID-19 “catch-up” package, intended to address this loss of learning. Since then, a new institutional framework has been rapidly created to implement this proposal: the National Tutoring Programme.

Of the £1 billion, the government is distributing £650 million directly to schools to help with catch-up as schools see fit, though the government strongly recommends spending it on small-group tutoring. The remaining £350 million goes straight to the NTP. Their progamme has two components: funding in-school academic mentors to provide intensive support, and providing subsidised access to tuition partners – existing tuition organisations. Both parts focus on disadvantaged children.

Catching up Implementing a tutoring system at scale is challenging. It requires recruitment, training, and the quality assurance of a large number of tutors, and it must ensure that the tutoring reaches those who need it.

The National Tutoring Programme has chosen to adopt a “platform service” model to meet these challenges. The platform allows for customers – schools – to be matched with suppliers – tutoring organisations.

This organisational form is well known. Examples such as Airbnb and Uber have proved to be efficient tools for matching supply with demand and incorporating quality review. One of the advantages of the platform approach is that it reduces the burden on any one organisation and distributes the risk of failure across many small organisations rather than a single large one. The risks in this case are the quality of the tutors and mentors.

It is very likely that the tutoring itself will raise skills: small group tutoring has been shown to be an effective method to help students who need extra support.

The question is whether the organisational form chosen to deliver this at large scale will work. There are good reasons for the approach chosen – but we do have some concerns.

First, it is vital that there is a strong link between the quality of a tutor organisation and the subsequent demand for its services. Unlike an organisation like Airbnb, local competition and repeated transactions might be too low to provide this link for a tutoring service.

The reliability of an accommodation option on Airbnb comes from the multiple, frequent reviews from a wide range of visitors. That kind of review base will not be available for a while. Furthermore, developing appropriate metrics for quality assurance will also take time. There will probably still be a need for bureaucratic quality review.

Second, what are the incentives for schools when they are thinking about purchasing and distributing tutoring time? For example, with free tutoring on offer, it seems likely (and understandable) that there will be pressure from some parents for their children to access the tutoring. However, it is also quite likely that these parents are not necessarily the parents of the children who most need it.

And then there is the sheer scale of the problem being addressed. In England, around 7 million children were in school before the first national lockdown and have been potentially affected by learning loss as a result of the pandemic.

This scale is too much for the current setup and current budget to address in full, meaning that many children will not achieve the skill levels that they might have hoped to at the end of their schooling. While £1 billion is a lot of money, dealing with this crisis fully will need more.

Indeed, while the National Tutoring Programme is among the first responses around the world to the pandemic learning loss, others suggest even greater action: in the US, leading educational researcher Robert Slavin has called for a large-scale “Tutoring Marshall Plan” to help heal the lost learning there.

While these issues must be kept under review, the National Tutoring Programme is undoubtedly a welcome initial response to the potentially enormous problem of lost skills in England. - 02-06-2020: "When should schools re-open?"

with Simon Burgess and Marta De Philippis

Economics Observatory

The Covid-19 crisis has required governments to make many difficult decisions, all fraught with risk. Among them is the re-opening of schools. This is complex because we lack so much key information. It is relatively easy to list the issues involved in the decision, as we do below, but much harder to quantify these factors – and even harder to weigh the costs and benefits of different options.

Why is it difficult to decide when to re-open?

Many governments decided relatively early on to get some children back at school: by late May, 22 European countries had re-opened schools. Naturally, this involves a health risk from potentially re-starting Covid-19 infection dynamics. But there are also other risks from not opening schools.

Health risks

While all countries will implement social distancing precautions and enhanced hygiene procedures in schools, greater contact is inevitable – between pupils, pupils and staff, pupils and other parents, both at school and during the commute to school. This in turn can take Covid-19 back to homes and communities.

The difficulty is that there is a lot of uncertainty about what the overall effect will be – for example, how easily do children transmit the virus to other children and to adults? Factors that will influence this include the initial level of infection, the density of population, the availability of space at school, as well as the accessibility of rapid response testing and tracing facilities at a local level (see John Hopkins, 2020).

Educational and inequality risks

The health risk is a key factor in this decision, but it is not the only one. Closing schools results in a loss of skills, and a consequent loss of productivity. Each week of school missed reduces the educational opportunities and achievements of millions of young people (Burgess and Sievertsen, 2020). These losses of skills matters for the future growth and prosperity of the country.

In addition, it is likely that the implications for educational outcomes will be strongly unequal. Experiences of education are now much more polarised than in normal times. Children in more disadvantaged families have less availability of digital devices and a fast internet connection at home. They are also more likely to live in overcrowded housing situations. In addition, less educated parents have probably less time and fewer skills to help their children in their home schooling activities (Bol, 2020).

Schools, moreover, are also important because they provide children with other facilities: food, company, sports and other physical activities. Countries and families face important long-term implications of skill loss and growing educational inequality.

Risks to parents’ work

Schools also offer child-minding services. A large-scale return to work, urgently needed to boost family incomes for those without work and to rebuild businesses, requires large-scale childcare. This is simply not possible without the schools being open, especially in countries with high female labour force participation. In the UK, around half of the workforce has at least one dependent child at home, and so business in general cannot re-open until the schools are open.

What strategies have different countries adopted?

The timing of re-opening schools strongly affects health risks, learning and educational inequality, and jobs, business and poverty. The weighing of these factors cannot be framed simplistically as ‘money versus lives’. Income loss, poverty and unemployment also affect health and influence mortality.

Many European countries have re-opened their schools, without apparent large increases in infection rates, although the re-opening so far has typically been for a small fraction of pupils, and only for a couple of weeks. An early overview of different countries’ policy responses on schools is provided by OECD/PISA, and the Johns Hopkins report provides details of policies on school return.

To illustrate the ways that governments are tackling this issue, here we discuss three countries that have taken very different decisions: Denmark, which only closed schools completely for one month; Italy, where schools will be closed till September; and England, where the situation remains unclear.

Denmark

On 10 March, Denmark had 262 confirmed Covid-19 cases. The day after, that number had risen to 514. In a reaction to this increase, the prime minister, Mette Frederiksen, announced the first set of lockdown measures, including the closure of all childcare institutions, schools, colleges and universities with effect from 13 March.

The number of Covid-19-related deaths in Denmark peaked at the end of April and the daily number of Covid-19 deaths has been below 10 since 1 May. But already on 6 April, the prime minister announced that childcare institutions and primary school (up to grade 5, children up to the age of 11) would open again on 15 April. On 7 May, it was announced that lower secondary schooling (up to grade 10, children up to the age of 16) would re-open on 18 May.

Children in Denmark do not return to the school day they used to know. The school day is structured such that children (and teachers) can maintain the generally advised distance (initially 2 meters, now 1 meter). Schools are encouraged to assign children to a small number of fixed peers to interact with during breaks and teaching, and to structure the teaching such that children have a minimum number of different teachers.

Italy

With the outbreak of the first coronavirus cases, schools were closed in the regions of Lombardy and Veneto where the first cases occurred (21 February). Then, some of the regions where infections were higher gradually announced temporary school closures. From 4 March, all schools were closed in Italy.

In the government’s initial announcement, the plan was to re-open schools by 15 March. But given the increased diffusion of the virus and the intensification of the lockdown measures, the re-opening date has continued to be postponed.

At present, primary schools, secondary schools and universities are expected to re-open, at least partially, only in September. All schools, apart from nurseries, are in any case usually closed in Italy for the summer break from the beginning of June to the beginning of September. The government is considering re-opening nurseries and summer childcare facilities earlier.

Few official details have been released so far on how in practice schools will re-open in September. The government has formed a taskforce in charge of advising on these issues.

In a decree approved in mid-May, the government announced that to tackle the Covid-19 emergency, they will hire many more teachers next year (increasing the number of teachers by 16,000). The government has also allocated funds for that period to provide digital devices to students in need for home schooling, equipment to ensure social distancing at school, and safety and health material to prevent the diffusion of the virus.

England

Schools in England officially closed on 20 March, although some had taken unilateral decisions to close before then. At that time, there was no official comment on a likely re-opening date, and many probably envisaged a very lengthy closure.

Two months on, as of late May, government policy is that some schools may be able to open from the 1 June on a partial basis, that is, for some of their pupils; but no schools are expected to open fully before September. The re-opening policy is explicitly conditional, depending chiefly on whether the rate of infection is continuing to fall.

The youngest children are in the initial wave of those returning: nursery, reception and year 1 children (those aged 4-6), plus year 6 children (those aged 10-11). The actual practicalities of teaching for these children are being worked out ‘live’, but they are intended to include all appropriate protective procedures including attempting distancing.

Secondary schools will not see a proper return to school before the summer holidays. They are expected to provide some limited ‘face-to-face activity’ for years 10 and 12, the two cohorts that will take exams for key high-stakes qualifications next year. There is currently very little guidance on what that activity should involve.

What does the future hold?

The message from contrasting developments in Denmark, Italy and England is probably representative of the global situation.

First, the strategy towards re-opening schools – in terms of both timing and how it should be done – will vary a great deal from country to country. It is not only the impact and timing of the Covid-19 pandemic that varies across countries, but also the institutional setting.

Important factors include medical and public health preparedness, the ability of schools to deliver effective online teaching, and the implications for schools of the labour supply of parents. For example, comparing the three countries discussed here: in Denmark in 2019, 84% of working households with dependent children have all adults working, in Italy the figures is 55% and in the UK 75%. The social and economic costs of keeping schools closed will vary equally substantially.

Second, children will not return to school as it was before the crisis, but to a ‘new normal’. That new normal is likely to include various measures to reduce infection risk with high demands on the children, their teachers and the school administrators. How long the new normal remains in place we cannot yet know. - 14-05-2020: "COVID-19: The expert economist view"

with Sarah Smith

Discover Economics

“Give me a one-handed economist”, demanded Harry Truman, the former US President. “All my economists tell me, on the one hand… but on the other …” Economists get a lot of stick when it comes offering diverging views. In a similar vein, George Bernard Shaw joked that if you laid all the economists in the world end to end, you wouldn’t reach a conclusion. Why do people love to mock economists’ ability to give a clear answer? Is it really the case economists can’t agree on anything?

The expert view

For nearly a decade, The Initiative on Global Markets (IGM) Forum at Chicago Booth Business School, has been asking leading economists for their views on topical economic issues. The expert panel consists of around 50 academic economists in the US and 50 academic economists in Europe who are at top institutions, including Harvard, Stanford, MIT, Berkeley, Yale, LSE, Oxford, UCL, Sciences Po, Trinity College Dublin, Bocconi, Stockholm. Each week, they are asked for their views on everything from climate change to BREXIT to the state of the economy to individual economic policies, such as the minimum wage. Their responses, across a nearly 400 questions that have been asked, provide a unique insight into how economists think about different issues.

The first thing to emerge from looking at the responses is that there is a high level of agreement among economists. Yes, that’s right – economists (broadly) agree! Very few economists vote against the consensus view on any topic – out of 100 economists that answer a question, only eight or so will express an opinion that is opposed to the majority view. On nearly one-third of the questions, there are no dissenting voices at all. Some of the issues on which economists are unanimous are that free trade generates net benefits to society, that imposing income taxes will cause a change in the tax base (by changing people’s actual behaviour or reporting patterns), that investors cannot out-perform the stock market on a persistent basis, that making drugs illegal increases their price and that not getting vaccinated against contagious diseases imposes costs on other people.

However, even expert economists are often reluctant to give a definite opinion. On each issue, the possible responses they can give are either (strongly) agree or (strongly) disagree, or to say they are uncertain. The “uncertain” response is chosen in nearly one-third of cases and by the majority of respondents on a range of issues including whether a tax on digital activities is a good idea, whether chief executives are paid too much, whether income tax cuts would increase GDP and whether local governments should curb gentrification. The one-handed economist problem is not so much that economists have evenly divided views on the same topic but that individual economists are often reluctant to give a firm view.

Why are economists uncertain?

One reason why economists are uncertain is when a question falls outside their specific area of expertise. Economics is a very broad subject covering many different “fields” and economists tend to specialise in one or two fields – international trade, development economics, the financial system, the macro-economy, labour economics, firm behaviour or government tax and spending policy. The panel members are 14 per cent more likely to give a definite answer (i.e. not answer uncertain) if the question falls within their area of expertise. If you want to find a one-handed economist, you are more likely to do so if you pick one in the right economic field to answer the question.

A second reason is that, in many cases, the questions the panel members are asked are not about economic models or economic evidence, which economists might more easily agree on, but are about whether something is “good for society”. Economic policies typically require trade-offs, imposing costs and benefits on different groups in society. Deciding whether a policy is a good idea (overall) means deciding whether the benefits to one group outweigh the costs to another. This involves making a value judgement that many economists may be reluctant to make. An economist can tell you what are some of the costs and benefits, but making the trade-off is a political judgement. Policy-making around COVID19 is no different. The government’s scientific advisors can provide the available facts and their best advice, but the science does not dictate a single course of action and ultimately the decisions, and the trade-offs, rest with the politicians.

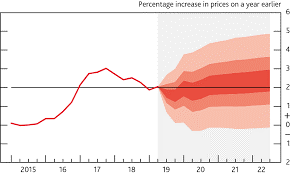

The third reason is that there is inherent uncertainty in many economic questions. Economists use economic models to understand and predict behaviour and economic data to validate – and fine-tune – their models. However, modelling something like the UK economy is hugely complex, involving the actions and interactions of millions of individual people and firms. The data that is available to measure what has happened may be imperfect, and, when it comes to predicting the future, simply not there. Ironically, economists are mocked just as much for making (over-precise) predictions about the economy as they are for their reluctance to reach a firm conclusion. “The only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable”, joked (economist) Ezra Solomon. Many self-respecting economists, recognising the inherent difficulties in looking into an economic crystal ball, are reluctant to give a precise answer. The Bank of England displays its predictions of future inflation rates using fan charts (an example is shown below) which show the range of price increases they expect – sometimes, being uncertain about exactly what the future holds is the only certain thing that economists can say.

Fan chart: Bank of England’s inflation projection

The chart shows the range of possible outcomes for future inflation rates. Based on the Bank of England’s model, the outturns of inflation are expected to lie within each shaded zone on 30 out of 100 occasions, implying a 90 per cent probability that inflation will lie (somewhere) within the fans.

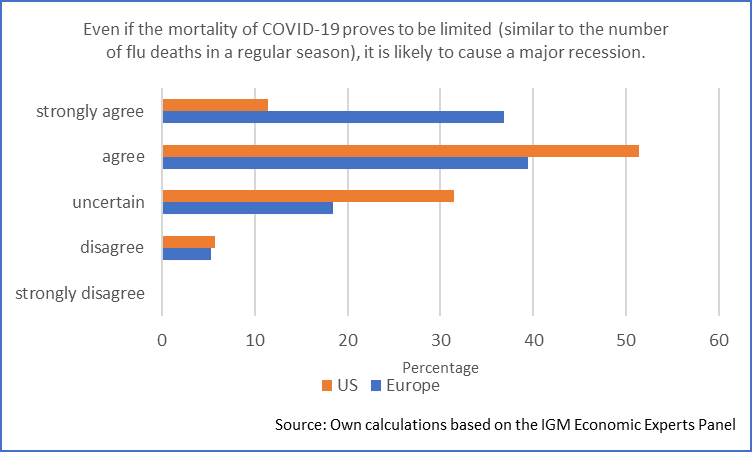

Expert views on COVID-19

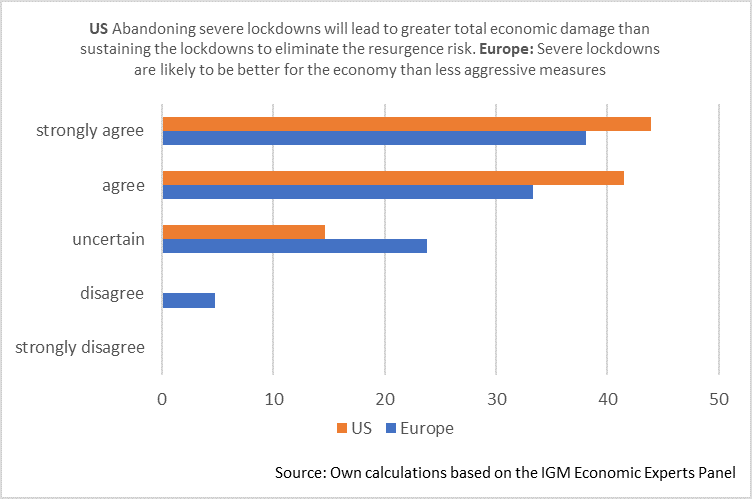

Currently the most pressing economic questions are about the impact of COVID19 on the economy and how to chart a way out of lockdown that will not trigger a second wave of the pandemic. The IGM Forum has asked its experts for their views on these topics. The answers show a very high degree of consensus among economists on both side of the Atlantic and a much higher degree of certainty than usual.

The first question asked in the second week of March (early in the pandemic) was about the likelihood of a recession. The responses are shown in the chart below. 76 per cent of the European expert economists and 63 per cent of US economists agreed that there would be recession. There were only dissenting two voices in each sample. Some were uncertain (nearly 20 per cent of the European sample and more than 30 per cent of the US sample, possibly higher in the US because the pandemic hit slightly later). But this level of uncertainty is notably lower than among the sample of all questions (one-third). Even in the early stages of the pandemic, there was a strong economic consensus, particularly in Europe, that a recession was on the cards.

Currently, governments in Europe and the US are grappling with how to ease lockdown. This has often been presented as a “economy versus health” questions – lockdown must be eased to get the economy going again, but this threatens a second wave of the pandemic. The views of the expert panel are that there may be less of a trade-off than is sometimes suggested and that coming out of lockdown too early poses an economic risk as well as a health one. 85 per cent of US economists and 71 per cent of European economists agreed that maintaining stricter lockdown was better for the economy in the medium term than coming out too early. There were few dissenting voices – and less uncertainty than on most other questions.

Take-aways

Economists are often mocked for not giving a clear opinion. Looking at the data, there is a very high degree of consensus among economists on many topics, but also a willingness among expert economists to admit they are uncertain. Uncertainty arises both because many economic questions are inherently complex and uncertain, making it hard to give precise answers, but also because economists are often asked questions that contain inherent value judgments that lie outside their economic expertise. When it comes to COVID19, however, there are plenty of “one-handed economists” – early on there was a clear consensus (with a high level of certainty) that the pandemic would cause a recession, also that coming out of lockdown too soon would have an even greater economic cost.

- 01-04-2020: "Schools, skills, and learning: The impact of COVID-19 on education"

with Simon Burgess

VoxEU

The global lockdown of education institutions is going to cause major (and likely unequal) interruption in students’ learning; disruptions in internal assessments; and the cancellation of public assessments for qualifications or their replacement by an inferior alternative. This column discusses what can be done to mitigate these negative impacts.

The COVID-19 pandemic is first and foremost a health crisis. Many countries have (rightly) decided to close schools, colleges and universities. The crisis crystallises the dilemma policymakers are facing between closing schools (reducing contact and saving lives) and keeping them open (allowing workers to work and maintaining the economy). The severe short-term disruption is felt by many families around the world: home schooling is not only a massive shock to parents’ productivity, but also to children’s social life and learning. Teaching is moving online, on an untested and unprecedented scale. Student assessments are also moving online, with a lot of trial and error and uncertainty for everyone. Many assessments have simply been cancelled. Importantly, these interruptions will not just be a short-term issue, but can also have long-term consequences for the affected cohorts and are likely to increase inequality.

Impacts on education: Schools

Going to school is the best public policy tool available to raise skills. While school time can be fun and can raise social skills and social awareness, from an economic point of view the primary point of being in school is that it increases a child’s ability. Even a relatively short time in school does this; even a relatively short period of missed school will have consequences for skill growth. But can we estimate how much the COVID-19 interruption will affect learning? Not very precisely, as we are in a new world; but we can use other studies to get an order of magnitude.

Two pieces of evidence are useful. Carlsson et al. (2015) consider a situation in which young men in Sweden have differing number of days to prepare for important tests. These differences are conditionally random allowing the authors to estimate a causal effect of schooling on skills. The authors show that even just ten days of extra schooling significantly raises scores on tests of the use of knowledge (‘crystallized intelligence’) by 1% of a standard deviation. As an extremely rough measure of the impact of the current school closures, if we were to simply extrapolate those numbers, twelve weeks less schooling (i.e. 60 school days) implies a loss of 6% of a standard deviation, which is non-trivial. They do not find a significant impact on problem-solving skills (an example of ‘fluid intelligence’).

A different way into this question comes from Lavy (2015), who estimates the impact on learning of differences in instructional time across countries. Perhaps surprisingly, there are very substantial differences between countries in hours of teaching. For example, Lavy shows that total weekly hours of instruction in mathematics, language and science is 55% higher in Denmark than in Austria. These differences matter, causing significant differences in test score outcomes: one more hour per week over the school year in the main subjects increases test scores by around 6% of a standard deviation. In our case, the loss of perhaps 3-4 hours per week teaching in maths for 12 weeks may be similar in magnitude to the loss of an hour per week for 30 weeks. So, rather bizarrely and surely coincidentally, we end up with an estimated loss of around 6% of a standard deviation again. Leaving the close similarity aside, these studies possibly suggest a likely effect no greater than 10% of a standard deviation but definitely above zero.

Impacts on education: Families

Perhaps to the disappointment of some, children have not generally been sent home to play. The idea is that they continue their education at home, in the hope of not missing out too much. Families are central to education and are widely agreed to provide major inputs into a child’s learning, as described by Bjorklund and Salvanes (2011). The current global-scale expansion in home schooling might at first thought be seen quite positively, as likely to be effective. But typically, this role is seen as a complement to the input from school. Parents supplement a child’s maths learning by practising counting or highlighting simple maths problems in everyday life; or they illuminate history lessons with trips to important monuments or museums. Being the prime driver of learning, even in conjunction with online materials, is a different question; and while many parents round the world do successfully school their children at home, this seems unlikely to generalise over the whole population.

So while global home schooling will surely produce some inspirational moments, some angry moments, some fun moments and some frustrated moments, it seems very unlikely that it will on average replace the learning lost from school. But the bigger point is this: there will likely be substantial disparities between families in the extent to which they can help their children learn. Key differences include (Oreopoulos et al. 2006) the amount of time available to devote to teaching, the non-cognitive skills of the parents, resources (for example, not everyone will have the kit to access the best online material), and also the amount of knowledge – it’s hard to help your child learn something that you may not understand yourself. Consequently, this episode will lead to an increase in the inequality of human capital growth for the affected cohorts.

Assessments

The closure of schools, colleges and universities not only interrupts the teaching for students around the world; the closure also coincides with a key assessment period and many exams have been postponed or cancelled.

Internal assessments are perhaps thought to be less important and many have been simply cancelled. But their point is to give information about the child’s progress for families and teachers. The loss of this information delays the recognition of both high potential and learning difficulties and can have harmful long-term consequences for the child. Andersen and Nielsen (2019) look at the consequence of a major IT crash in the testing system in Denmark. As a result of this, some children could not take the test. The authors find that participating in the test increased the score in a reading test two years later by 9% of a standard deviation , with similar effects in mathematics. These effects are largest for children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Importantly, the lockdown of institutions not only affects internal assessments. In the UK, for example, all exams for the main public qualifications – GCSEs and A levels – have been cancelled for the entire cohort. Depending on the duration of the lockdown, we will likely observe similar actions around the world. One potential alternative for the cancelled assessments is to use ‘predicted grades’, but Murphy and Wyness (2020) show that these are often inaccurate, and that among high achieving students, the predicted grades for those from disadvantaged backgrounds are lower than those from more advantaged backgrounds. Another solution is to replace blind exams with teacher assessments. Evidence from various settings show systematic deviations between unblind and blind examinations, where the direction of the bias typically depends on whether the child belongs to a group that usually performs well (Burgess and Greaves 2013, Rangvid 2015). For example, if girls usually perform better in a subject, an unblind evaluation of a boy’s performance is likely to be downward biased. Because such assessments are used as a key qualification to enter higher education, the move to unblind subjective assessments can have potential long-term consequences for the equality of opportunity.

It is also possible that some students’ careers might benefit from the interruptions. For example, in Norway it has been decided that all 10th grade students will be awarded a high-school degree. And Maurin and McNally (2008) show that the 1968 abandoning of the normal examination procedures in France (following the student riots) led to positive long-term labour market consequences for the affected cohort.

In higher education many universities and colleges are replacing traditional exams with online assessment tools. This is a new area for both teachers and students, and assessments will likely have larger measurement error than usual. Research shows that employers use educational credentials such as degree classifications and grade point averages to sort applicants (Piopiunik et al. 2020). The increase in the noise of the applicants’ signals will therefore potentially reduce the matching efficiency for new graduates on the labour market, who might experience slower earnings growth and higher job separation rates. This is costly both to the individual and also to society as a whole (Fredriksson et al. 2018).

Graduates

The careers of this year’s university graduates may be severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. They have experienced major teaching interruptions in the final part of their studies, they are experiencing major interruptions in their assessments, and finally they are likely to graduate at the beginning of a major global recession. Evidence suggests that poor market conditions at labour market entry cause workers to accept lower paid jobs, and that this has permanent effects for the careers of some. Oreopoulos et al. (2012) show that graduates from programmes with high predicted earnings can compensate for their poor starting point through both within- and across-firm earnings gains, but graduates from other programmes have been found to experience permanent earnings losses from graduating in a recession.

Solutions?

The global lockdown of education institutions is going to cause major (and likely unequal) interruption in students’ learning; disruptions in internal assessments; and the cancellation of public assessments for qualifications or their replacement by an inferior alternative.

What can be done to mitigate these negative impacts? Schools need resources to rebuild the loss in learning, once they open again. How these resources are used, and how to target the children who were especially hard hit, is an open question. Given the evidence of the importance of assessments for learning, schools should also consider postponing rather than skipping internal assessments. For new graduates, policies should support their entry to the labour market to avoid longer unemployment periods.

References

- Andersen, S C, and H S Nielsen (2019), "Learning from Performance Information", Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory.

- Bjorklund, A and K Salvanes (2011), “Education and Family Background: Mechanisms and Policies”, in E Hanushek, S Machin and L Woessmann (eds), Handbook of the Economics of Education, Vol. 3.

- Burgess, S and E Greaves (2013), “Test Scores, Subjective Assessment, and Stereotyping of Ethnic Minorities”, Journal of Labor Economics 31(3): 535–576.

- Carlsson, M, G B Dahl, B Öckert and D Rooth (2015), “The Effect of Schooling on Cognitive Skills”, Review of Economics and Statistics 97(3): 533–547

- Fredriksson, P, L Hensvik, and O Nordström Skans (2018), "Mismatch of Talent: Evidence on Match Quality, Entry Wages, and Job Mobility", American Economic Review 108(11): 3303-38.

- Lavy, V (2015), “Do Differences in Schools' Instruction Time Explain International Achievement Gaps? Evidence from Developed and Developing Countries”, Economic Journal 125.

- Maurin, E and S McNally (2008), "Vive la revolution! Long-term educational returns of 1968 to the angry students", Journal of Labor Economics 26(1): 1-33.

- Murphy, R and G Wyness (2020), “Minority Report: the impact of predicted grades on university admissions of disadvantaged groups”, CEPEO Working Paper Series No 20-07 Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunitites, UCL Institute of Education.

- Oreopoulos, P, M Page and A Stevens (2006), “Does human capital transfer from parent to child? The intergenerational effects of compulsory schooling”, Journal of Labor Economics 24(4): 729–760.

- Oreopoulos, P, T von Wachter, and A Heisz (2012), "The Short- and Long-Term Career Effects of Graduating in a Recession", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4(1): 1-29.

- Piopiunik, M, G Schwerdt, L Simon and L Woessman (2020), "Skills, signals, and employability: An experimental investigation", European Economic Review 123: 103374.

- Rangvid, B S (2015), "Systematic differences across evaluation schemes and educational choice", Economics of Education Review 48: 41-55.

- 31-03-2020: "The long-term consequences of missing a term of school" with Simon BurgessIZA World of Labor

The Covid-19 pandemic is first and foremost a health crisis. Many countries have (rightly) decided to close schools, and teaching is moving online, on an untested and unprecedented scale.

From an economic point of view the primary point of being in school is that it increases a child’s ability; even a relatively short period of missed school will have consequences for skill growth. We cannot estimate precisely the impact of the Covid-19 interruption on learning as we are in a new world, but we can use other studies to get an order of magnitude.

In a Swedish example, young men had differing numbers of days to prepare for important tests. These differences were conditionally random, allowing the authors to estimate a causal effect of schooling on skills. Even just ten days of extra schooling significantly raised scores on tests of the use of knowledge (“crystallized intelligence”) by 1% of a standard deviation (SD). As an extremely rough measure of the impact of the current school closures, if we were to simply extrapolate those numbers, 12 weeks less schooling (60 school days) implies a loss of 6% of an SD, which is non-trivial. The authors do not find a significant impact on problem solving skills (an example of “fluid intelligence”).

A different way into this question is a study that estimated the impact on learning of differences in instructional time across countries. Perhaps surprisingly, there were very substantial differences between countries in hours of teaching. Less surprising is that these differences matter: one more hour per week over the school year in the main subjects increases test scores by around 6% of an SD. In our case, the loss of perhaps three to four hours per week of teaching in maths for 12 weeks may be similar in magnitude to the loss of an hour per week for 30 weeks. So, surely coincidentally, we end up with an estimated loss of around 6% of an SD again. Leaving the close similarity aside, these studies possibly suggest a likely effect no greater than 10% of an SD but definitely above zero.

Families are widely agreed to provide major inputs into a child’s learning. The current global-scale expansion in home schooling might at first thought be seen quite positively, as likely to be effective. But typically, the families’ role is seen as a complement to the schools’ input. Being the prime driver of learning, even in conjunction with online materials, is a different question; and while many parents round the world do successfully school their children at home, this seems unlikely to generalize over the whole population.

Global home schooling will surely produce some inspirational moments, some angry moments, some fun moments and some frustrated moments, but it seems very unlikely that it will on average replace the learning lost from school. The bigger point is this: there will be substantial disparities between families in the extent to which they can help their children learn. Key differences include: the amount of time available to devote to teaching, the non-cognitive skills of the parents, resources (for example, not everyone will have the kit to access the best online material), and also the amount of knowledge—it’s hard to help your child learn something that you may not understand yourself. Consequently, this episode will probably lead to an increase in the inequality of human capital growth for the affected cohorts.

- 21-10-2016: "Konsekvenser af børnefattigdom–hvad ved vi egentlig?"

with Torben Tranæs

Berlingske Tidende

Policy writing

-

Whenever possible, the titles are links to the articles.